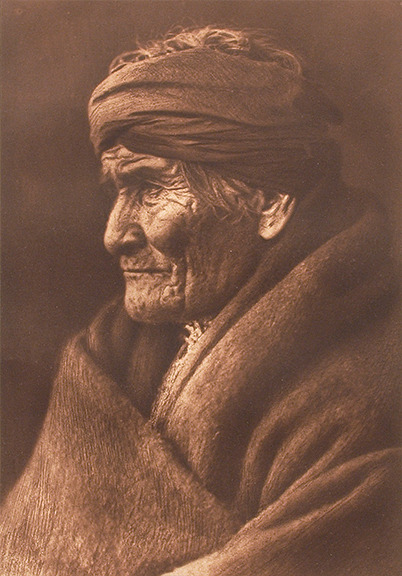

(Michel Witmer, a collector in New York City, was persuaded to buy a work by Pierre-Auguste Renoir, an artist he had never liked, at a museum show. | BENJAMIN NORMAN FOR THE NEW YORK TIMES)

FOR most art lovers, museums are a place to indulge a passion or seek solace from the world outside. But for art collectors like Jorge Garcia, they offer a level of objectivity about an artist’s work that galleries lack.

Not to mention what a museum curator’s imprimatur can do to the value of the art.

Mr. Garcia, a regional sales manager in Miami for an environmental consultant, says that before he buys artworks — and he has bought hundreds — he studies the artists to find out where they are from, where they studied art, what shows they have had and which gallery represents them.

But then, Mr. Garcia says, he goes further. He looks at the museum shows the artists have had, or better yet, those they are scheduled to have.

“The contemporary art market is investment-driven,” he said. “There’s a lot of demand. But it doesn’t mean all of these artists are going to be around in 10 or 15 years.”

He goes to galleries to buy works of art, but if that is all the artists have on their résumés, he asks himself, “Is it just gallery, gallery, gallery — commercial, commercial, commercial?”

Grela Orihuela, the director of Art Wynwood and a consultant for Art Miami, two art fairs in Miami, agreed that “a museum show can change the reputation of an artist.”

She added: “A museum show can be very influential for an artist. It changes the price point, the popularity, the awareness a person has for an artist.”

She pointed to Frank Stella, a painter who had a retrospective show last fall at the Whitney Museum of American Art. The show ran for a little more than three months, and after it closed, the value of his existing work rose — even though Mr. Stella has been a well-known American artist since the 1960s.

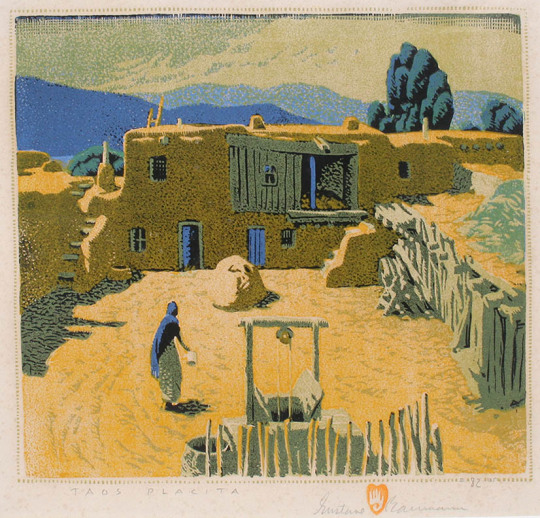

This winter, the Coral Gables Museum in Florida is staging an exhibition of Cuban art in the 20th century. And in an attempt to similarly capture collectors’ interest in the artists exhibited there, Ms. Orihuela said, Art Wynwood is staging shows of both established and younger Cuban artists.

“We have a gallery that will do all our fair, and I’ve confirmed that the prices will be different with Art Wynwood 2017 because of this show,” she said.

Dr. Julio Ortiz, an eye surgeon in Miami, has seen the effect. He said he bought pieces by the Cuban artist Roberto Fabelo for $30,000 a few years ago. But after his work was shown in museums in the United States and Europe, similar works fetched $100,000.

“I wouldn’t say the quality is so different, but there’s more demand,” Dr. Ortiz said.

Using museum shows to inform investments is not limited to living artists. Michel Witmer, a collector in New York City, said a show at the Philadelphia Museum of Art that was centered on the painters represented by Paul Durand-Ruel, a Parisian art dealer at the turn of the 20th century, persuaded him to buy a work by Pierre-Auguste Renoir, an artist he had never liked.

“When I went to the Durand-Ruel show, I got to learn more about Renoir and why he was so important,” he said.

Shortly after the show, he bought a Renoir at auction. “I wouldn’t have bought that piece if I hadn’t seen the show,” he said.

It may seem odd that it took a museum show to persuade a collector with the means to buy a Renoir to buy one at last. But Mr. Witmer disagreed.

“I have a home in Greenwich, and I’m fond of my friends there,” he said. “But there are people who want to buy something because they’ve seen it in the homes of well-known collectors. Going to shows in museums helps us become better individual art collectors.”

Researching artists through their museum shows, with the expectation that the prices for their art are going to soar, is a bit like private equity investing. Some pieces may take off. Others may maintain their value. But for some, the market to resell the works may dry up.

Mr. Garcia said this had happened to him. “I’ve bought stuff and I can’t sell it today,” he said. “You can’t predict. They’re contemporary artists. But I still like it.”

Nevertheless, he said, it’s worth the risk. As a comparatively small collector, he said, if he did not buy a work early, he could be priced out or excluded from buying a work even if he could afford it. “If a major collector comes in from New York or London, he’s going to get first dibs over me,” he said.

Art collectors also have the option of lending their art to museums to increase the value of their works. Ramón Cernuda, a collector of Cuban art who sold his publishing company and opened an art gallery in Coral Gables, Fla., said he had about 350 works of art but could display only about a third of the collection.

Right now, seven or eight of his paintings by Wifredo Lam, among the best-known Cuban painters, are part of a traveling retrospective that is now at the Tate Modern in London. Another 60 pieces by various artists are on loan to the art museum at Florida State University.

“We did this at first for the opportunity for other people to enjoy the artworks and for other people to learn about the artists,” he said.

But Mr. Cernuda said he understood the financial impact of his loans. “In general, it enhances value,” he said. “There is a direct relationship between value and exhibition — museums being the highest level of exhibition prestige for an artist or an artwork.”

Still, lending artworks in the hope that a museum show will increase their value carries risks.

“People who buy art and exhibit it around the world to increase its value do it because they’re told it’s going to increase the value,” said Diana Wierbicki, global head of the art law practice group at Withers Worldwide. “Their hesitations on it always come down to an insurance issue.”

One risk is that a piece will be damaged, leading to a claim for a partial loss of value. “The insurance company comes back and says it’s a 20 percent loss,” she said. “But we could say it’s a 30 percent or 40 percent loss.”

Another risk is that a work of art will be seized while on loan internationally. (A work can be seized if a country or person claims it, but it could also be taken to pay a debt.) Ms. Wierbicki said an insurance policy could include coverage against seizure, but whether the policy is enforceable depends on the country where the work has traveled.

If the insurance can be worked out, the benefits of art loans to museums can be immense. Mr. Cernuda said that after the Lam show opened last fall at the Centre Pompidou in Paris, the value of the artist’s work at auction jumped over 80 percent.

“There is a very direct and inevitable link between the market and museum exhibitions,” Mr. Cernuda said.

And chasing that link will surely drive some collectors this fall.