THE TIT PAINTINGS

Brigid Berlin’s technique for her Tit paintings consisted of dipping her tits in paint and then pressing them down onto canvas. When she performed this live at the Grammercy International Art Fair, one of the spectators was filmmaker John Waters:

John Waters:

I think that she’s the most un-selfconscious nude person. I mean I’ve never been nude – I really take a bath in my underpants. But when I saw Brigid doing her tit painting – she just took off her blouse and started, you know, using her tits as painting. She said this is totally not about nudity, this is about, you know, art. (BB)

The Tit paintings were exhibited by Jane Stubbs at a gallery on Madison Avenue in 1996. Also on exhibit were Brigid’s pillows stuffed with cut-out penises. (ST)

Jane Stubbs:

Brigid would cut them out of muscle magazines while she was watching the OJ trial. She got very involved in the trial and she took out her frustrations on thousands of men, thousands of penises. I mean it was quite mad. (BB)

Brigid Berlin: “My mother wanted me to be a slim respectable socialite… Instead I became an overweight troublemaker.” (ST/BB)

Brigid Berlin was born on September 6, 1939. Her parents were Richard E. Berlin, the chairman of the Hearst media empire for 52 years, and socialite “Honey” Berlin, whose real name was Muriel. Richard was 22 years older than Honey who was 21 at the time of their marriage. Brigid was born approximately nine months later. Brigid’s sister, Richie, was born after Brigid, followed by another sister, Christina, and then a brother, Richard. Richie, who was named after her father, sometimes hung out with Brigid in New York and also appeared briefly in the non-Warhol film, Ciao Manhattan. Brigid’s other sister, Christina, arranged the defection of the Russian ballet dancer, Mikhail Baryshnikov. When Richard Berlin found out about his daughter’s involvement with Baryshnikov, he wasn’t pleased. Brigid recalls: “I remember Daddy went nuts – ‘If she marries that commie bastard…!'” (NYO)

Brigid Berlin:

Mother was a New York society girl… She smoked. She didn’t read books… She went to every fashion show because Daddy ran the show at Hearst… He got the company out of debt; he sold off newspapers to buy television stations. When Patty Hearst was kidnapped, he held the purse strings, and he was reluctant to give up the ransom money to get her back… At our apartment, at 834 Fifth Avenue, my mother had needle-point thrones, not toilets – very French. My mother slept with her makeup on. When I was 10 years old I found her Tampax, and she told me they were for removing makeup. So every night I cleansed my face with cold cream and Tampax. She had plastic vibrators, and she told us they were for her neck. I cannot picture her having sex. She wore heels at home – in the house, for Christ’s sake!… My mother didn’t work… She got her hair done every day, over at the House of Charm on Madison and 61st Street. When I was 11, she gave me a permanent. (NYO)

Brigid Berlin’s parents were very “up there” – a term that Warhol would later use to describe the socially advantaged. Her family’s friends included major Hollywood celebrities and world leaders:

Brigid Berlin:

I would pick up the phone and it would be Richard Nixon. My parents entertained Lyndon Johnson, J. Edgar Hoover, and there were lots of Hollywood people because of San Simeon – Clark Gable, Joan Crawford, Dorothy Kilgallen… I have a box of letters, written to my parents in the late 1940’s and 1950’s from the Duke and Duchess of Windsor. (Ibid)

Honey Berlin was constantly trying to get Brigid to lose weight as a child, giving her cash for every pound she lost and pharmaceutical “speed” to help her lose it. Brigid was sent to the family doctor at the age of eleven to get amphetamines and dexedrine (little orange hearts), while her mother took Preludin. According to Brigid, “Everyone was doing it. Jack and Jackie Kennedy went to Max Jacobson’s.” (NYO) Max Jacobson was the doctor famous for his vitamin B shots laced with speed.

Brigid Berlin:

My mother used to go to Papillon and the Colony and have three asparagus spears. She was a one-spoonful gal. Not me! She used to take us to Paris, but she spent her whole time in couture fittings, so my sister and I ran around Paris eating…They all ate like birds, so I started to sneak the uneaten food in the middle of the night. (NYO)

At the age of 16, Brigid was sent to a school in St. Blaise, Switzerland to lose “50 pounds” but she would “pilfer the other girls’ money and go on pastry binges… My roommate and I decided to get drunk. I got so fucking wasted I was doing Indian dances. I woke up the next day, and there was shit on the floor next to my bed. One of the mademoiselles entered the room and demanded, ‘Qu’est-ce que c’est que ca?’ I said, ‘C’est le chien,'” blaming it on the dog. “She said ‘C’est trop grand!’ They they wrote home to my parents and told them I was using my bedroom as a toilet.” (Ibid)

Brigid completed her education at the Convent of the Sacred Heart Eden Hall in Pennsylvania, a Catholic school where her father had sent her, saying “At least you’re not going to get Communism from the nuns!” (Ibid)

According to Brigid in the film about her life, Pie In the Sky, her father used to donate Italian Madonna and child paintings to the school to prevent herself and her sister, Richie, from getting thrown out. The only subject that Brigid ever passed was penmanship. (BB)

During school holidays, Brigid worked at Harpers Bazaar which was published by the Hearst Corporation. Her job was to detach the dollar bills that people sent in with letters requesting the Harper’s Bazaar Beauty Box. (NYO)

BRIGID BERLIN COMES OUT

After finishing her schooling, Brigid Berlin returned to New York for her coming-out party: “I was a debutante, so I needed two escorts. My mother went crazy when I invited the electrian who was working on our TV wires at our house in Westchester” as one of the escorts. She then moved to Manhattan, hanging out with people like Wendy Vanderbilt and George Hamilton – “I think I spent the night with him – I’m not sure” – and going out to places such as Michael II’s on 70th Street, Malachy McCourt’s bar on Third Avenue (owned by the brother of Frank McCourt) and Clavins, opposite the first Serendipity. (NYO)

She went to Dr. Freiman for speed injections – who was often referred to as Dr. Feelgood. Brigid later described what would then happen: “He took my Hermes scarf off and blindfolded himself and said, ‘I’m going to make you feel better than any man has made you feel.’ His shots were amphetamine, diuretic and B12. By then I was 19 and very high, and my sister and I would go straight to Bloomie’s and start charging.” (Ibid)

BRIGID BERLIN’S GAY HUSBAND

At the age of 21 she married a gay window trimmer, John Parker, who worked at a store on 57th and Fifth named The Tailored Woman. According to Brigid, Parker “had the deepest windows in town. I knew all the window-dressers up and down the avenue – Joel Schumacher, Gene Moore.” Parker and Brigid stole her father’s Cadillac and drove to Cherry Grove, Fire Island where they rented a house and renamed it Brigadoon. She would travel to Manhattan on the seaplane to pick up checks, to shop and to check on the apartment at 65th Street. She recalls: “I hung out with all these piss-elegant queens… I was insane, but also very grand. I went through $100,000, and my mother went beserk.” (NYO)

Andy Warhol (via Pat Hackett in Popism):

When Brigid brought her window dresser fiance home to meet the family, her mother told the doorman to tell him to wait on a bench across the street in Central Park. Then she handed Brigid her wedding present – a hundred dollar bill – and told her to to to Bergdorf’s and buy herself some new underwear with it. Then she added, ‘Good luck with that fairy’. (POP104)

The marriage to John Parker dissolved when the money was gone, Brigid having failed to turn her husband into a straight man, although they did have sex. (BB)

REHAB

After the break up, Brigid’s father’s friend, Lyndon Johnson, got her into a rehab facility in Mexico to lose weight, letting her mother take care of Brigid’s first pug – a gift from Sylvia Sidney. The hospital was the first that was experimenting with fasting. Although Brigid had to take a daily urine test to make sure she wasn’t eating, she cheated by putting nail polish in her urine, thinking that one of the drugs in the nail polish was the same one produced by the body to indicate fasting. While in the hospital she had an affair with one of the psychologists and two of the doctors.

Brigid Berlin:

But I ended back up in New York with the plan of getting another job – but not knowing how to type and basically not having any interest in anything except shopping and staying out all night. (BB)

BRIGID MEETS ANDY

After returning to New York, Brigid ended up living at the Chelsea Hotel on West 23rd Street in what she now remembers as Room 907. In Popism, Andy Warhol described Brigid’s life at the Chelsea: “Brigid swore that she never went into her own room there more than once a week – the rest was just in-house visiting, running from room to room…” (POP175)

Although she had already seen Warhol around New York, in approximately 1964 Henry Geldzahler took her to the (silver) factory and she became part of the scene there. She was nicknamed Brigid Polk because of the “pokes” she liked to give herself and others – injections of speed.

Warhol and Brigid became close friends, with Andy ringing her daily. She was the main “B” in Warhol’s book, Andy Warhol’s Philosophy (From A to B and Back Again) – although “B” really represented any of the people he spoke to regularly on the phone. She would also go shopping with him or watch movies together (Brigid: “I didn’t like the kind of TV that Andy liked. His favorite show was I Dream of Jeannie/) (I11)

Brigid Berlin:

Andy and I didn’t go out that much together. We’d spend our time talking on the phone. He use to call me up in the morning – he always talked about his health with me. I think I was the health person. There were other people he used for different topics. And he’d say all of a sudden out of the clear blue – ‘Brige, my balls are sore… [Brigid would reply:] ‘Oh god Andy, c’mon, I don’t know anthing about sore balls. (BB)

Brigid was known for her obsessive tape recording and Polaroid taking. She tape recorded “everything” from 1967 – 1974, taking pride in the quality of her recordings – “I always had the best microphones, you know”. A tape she made of the Velvet Underground performing at Max’s was so good that Atlantic made it into an album. (I11)

Andy Warhol (via Pat Hackett in Popism):

I guess it was all the mechanical action that was the big thing for me at the Factory at the end of the sixties… The big question that everyone who came by the Factory was suddenly asking everyone else was ‘Do you know anyone who’ll transcribe some tapes?’ Everyone, absolutely everyone, was tape-recording everyone else. Machinery had already taken over people’s sex lives – dildos and all kinds of vibrators – and now it was taking over their social lives, too, with tape recorders and Polaroids.The running joke between Brigid and me was that all our phone calls started with whoever’d been called by the other saying, ‘Hello, wait a minute’ and running to plug in and hook up.’ (POP291)

The conversations that Brigid Berlin taped between herself and her mother were the basis for Andy Warhol’s play in the early seventies, Pork. Brigid sold the tapes to Warhol for $25.00 each. (BB)

Brigid was infamous for her telephone calls – some were featured in Warhol’s film The Chelsea Girls. In 1968 she performed a “mixed media” event – at the Bouwerie Lane Theatre called Bridget Polk Strikes! Her Satanic Majesty in Person, in which she made phone calls to friends from the stage and broadcasted the live conversations to the audience, without telling the person she was talking to over the phone – which included Huntington Hartford and her parents. (Ibid)

ANDY FILMS BRIGID

Brigid Berlin appeared in various Warhol films and video projects including The Chelsea Girls (1966), Bike Boy (1967), Imitation of Christ (1967), **** (1967), The Loves of Ondine (1967), The Nude Restaurant (1967), Tub Girls (1967), Phoney (Video – 1973), Fight (Video – 1975) and Andy Warhol’s Bad (1976). She was also originally scheduled to appear in Lonesome Cowboys. She also appeared in the non-Warhol film, Ciao Manhattan with Edie Sedgwick and made a cameo appearance in John Water’s film Serial Mom (1994) – on the set for which she met and befriended Patricia Hearst – the daughter of her father’s old “boss”, William Randolph Hearst, and ex-member of the Symbionese Liberation Army. Brigid also appeared in John Waters’ Pecker (1998).

THE COCK BOOK

Brigid was also known for her own art projects – her “trip” books from the sixties, her Polaroids and her “tit” paintings.

Brigid Berlin:

When we were all on amphetamine in the sixties this is what we used to do – would be to draw in our trip books and I could spend my life drawing circles and filling the circle with circles and more dots and more circles around it and then coloring them all with Doctor Martin’s watercolor dyes. (BB)

When she came across a large book full of blank pages with the title, Topical Bible, at a shop on Broadway, she decided to use it as a trip book and wanted to choose a theme for it. “Topical” ryhmed with “cockical” so she made it into a cock book. In addition to drawing in it herself, she would take it with her to Max’s or the Factory and get whoever was around at the time to make a cock drawing in the book. Among the people who contributed to the book were Taylor Mead, Billy Sullivan, Jasper Johns, Robert Rauschenberg, Jane Fonda, Roger Vadim, Peter Beard, Dennis Hopper, Ondine, Richard Avedon and Leonard Cohen. (ibid)

Brigid also did other trip books, including the scar book – “snapshots of welts from all over town”. (ST)

THE POLAROIDS

Gerard Malanga:

Brigid Polk was doing Polaroids in 1969 and 1970. Heiner Friedrich did a little show of her work. I think the show was called Tapes and Polaroids. (AWP116)

What made Brigid’s Polaroids unique was that she often double exposed them which had not been done previously – the technology didn’t exist. When Polaroid brought out a camera that enabled double exposures, Brigid took full advantage of it when photographing others or herself – double exposed self portrait Polaroids.

DRUGS

Brigid continued to drink and take drugs in the early seventies: She recalls: “In the early 70s, I went to Woolworth’s and bought a jigger so I could have just one getting-dressed drink. By the time I left the house, I’d had 20. One time, I was in a hairdresser under the dryer getting bored. I went to the bar across the street in my rollers and had a glass of white wine. Then another glass of wine and another. I can’t remember anything else until I woke up in a Howard Johnson near La Guardia Airport. And there were pancakes and maple syrup. There was a cute boy in the room watching Kids Are People Too. I think I thought that Andy would put him on the cover of Interview. He didn’t.” (NYO)

After numerous unsuccessful attempts, Brigid eventually cleaned up through twelve step fellowships in the mid-late 80s and still deals on a daily basis with her addiction to food. Her drugs of choice were speed and Majorska vodka. (I11)

THE FACTORY

Brigid Berlin became a permanent employee at the Factory in 1975, working at the front desk and transcribing interviews, and continued working there in the eighties.

Brigid Berlin:

I would transcribe interviews, and then for many years I didn’t do anything. I used to knit and needlepoint under the desk. It wasn’t like a job, so that’s why I stayed there so long. I was the first one there in the morning, but as soon as I got there I would watch the clock all day till I could leave. And every year I left five minutes earlier, and Andy used to look down at his watch and say ‘Where are you going?’ I’d say, ‘I’m going home.’ ‘Well, the fun’s just beginning,’ he’d say. And then he’d give me a hundred dollars and tell me to go to the liquour store and get some Irish whiskey and I’d come back and make Irish coffee, get smashed, tell Andy he was a slob and that I hated him. (I11)

The year prior to working at the Factory was spent as a recluse in her New York apartment, losing weight. By living on “bouillon and tea” she managed to lose 160 pounds in a year. At home she would cut out press clippings of Warhol which she would sell to him for 50 cents a clipping.

Dimitri Ehrlich, an employee at Interview magazine, later described his first impression of Brigid when he started working there in 1988:

In 1988, when I first started working at Interview, the magazine was still housed in the last of the Warhol factories. On my first day at work, I noticed two small pugs who seemed to have the run of the castle. They belonged to a woman who sat behind the front desk every day from 9:00 to 5:00, but who never seemed to answer the phone. Instead, she compulsively knitted, ate bags of candy and tended lovingly to the dogs. A few months later I learned that this mysterious woman was Brigid Berlin. (Ill)

HONEY DIES

Eventually, Brigid’s father, Richard E. Berlin contacted Alzheimer’s disease. Brigid recalls: “Daddy’s Alzheimer’s was really fun. He denied everything – ‘You’re not my children!’ – and gave my gay sister’s girlfriend a cigar when she came over.” (NYO)

Her mother, Honey Berlin, died four months after Andy Warhol: “In 1986, she [Honey] was lying in her bed, dying of cancer, and she was still calling the saleswomen to get new Adolfo’s at the Saks in White Plains. She had them hung on her door so she could look at them.” When Honey died, Brigid reacted by going “upstairs with two pocketfuls of Toll House cookies and started going through her jewelry.” (ibid)

BRIGID NOW

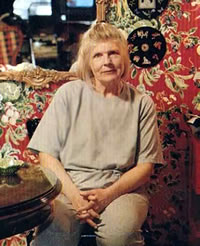

Brigid Berlin (2001)

In January 1998, Brigid perfomed another stage show – a monologue about one of her obsessions – cleaning products. According to Daisy Garnett in the Sunday Telegraph magazine, “It was a performance which people talk about having seen with a certain smugness, the way they might boast about having seen Talking Heads at CBGBs in 1975.” (ST)

Brigid Berlin still lives in New York “a few blocks north of Manhattan’s fashionable Grammercy Park” (ibid) She has two pugs named India and Africa: “I don’t like it when they call them ‘dogs’ – they are my children. I have to have a car and a driver; I want them with me. Every day we stop at Grace’s Market and get chicken breasts.” (NYO)

BRIGID RELAPSES

Brigid Berlin relapsed on alcohol in about 2006. She was admitted into rehab at CARON (Comprehensive Addiction Treatment Recovery for Life) in Pennsylvania on August 26, 2007 and Silver Hill Hospital in Connecticut in 2008.

Brigid Berlin [2008]:

… I didn’t have a drink for 17 years. I thought my life was pretty good and I was pretty happy. And then three years ago this month, I was just walking the dogs around the block like I did every night and something ticked me off that I wanted fettuccini Alfredo. I went into a restaurant down the block and I had the dogs, and they didn’t want to let me in, but there was this tiny table in front, and I said, ‘If I sit really near the window, they’re not going to bite anybody. Can I just get this takeout order?’ And I ordered a glass of Pinot Grigio out of nowhere… (VF)

BRIGID GETS PUBLISHED

Brigid Berlin, Gerard Malanga, Vincent Fremont and Bob Colacello (plus the back of the front row heads of sociologist Victor P. Corona, author Thomas Kiedrowski and Ben House)

In 2015 Reel Art Press published an (excellent) collection of Brigid’s Polaroids. The Strand bookstore held a panel discussion with Brigid, Gerard Malanga, Vincent Fremont and Bob Colacello in conjunction with the book. It can be seen on YouTube here.